Minsk could be a short-term beneficiary, but the already high chances of Belarus’ absorption by Russia would only increase.

The Kremlin pinned serious hopes on the Istanbul Accords in March and April 2022 as a first step toward its key goal of pulling Ukraine back into Moscow’s orbit.

Istanbul 2022 would undermine the foundations and principles of Ukrainian statehood and be a triumph for Moscow, but for Kyiv it would be not even Minsk-2015, but “Munich-1938.

Alaksandar Łukašenka could act as a peacemaker and guarantor, but it did not work out.

WSJ reveals details of Istanbul Accords

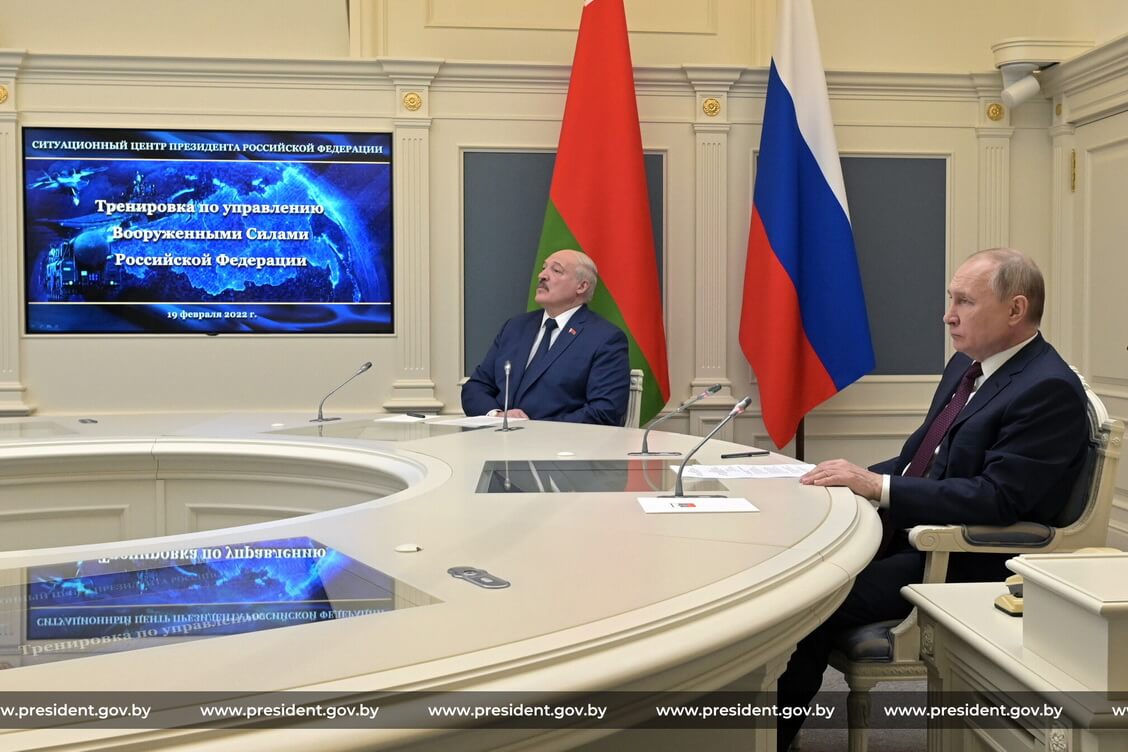

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Łukašenka often recall the negotiations between Russia and Ukraine, which took place in March-April 2022 and culminated in drafting the Istanbul Accords.

While Łukašenka casts himself a peacemaker and potential mediator in the peace talks, the Russian ruler uses the Istanbul theme mainly for propaganda, accusing Kyiv and the West, especially former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, of blocking the allegedly noble peace initiative.

Ukrainian officials have also confirmed that Kyiv and Moscow were close to striking a deal in 2022, but would not disclose any details.

The Istanbul Accords called for Ukraine’s neutral status and its refusal to join NATO, reported the Wall Street Journal (WSJ).

Ukraine would have its armed forces reduced to 85,000 troops, would be allowed to have a limited number of conventional weapons and banned from using foreign military equipment.

The Kremlin also demanded the recognition of Russian as a second state language in Ukraine, a ban on International Criminal Court investigations into Russia’s war crimes and the recognition of Crimea as part of Russia.

Status of other Russian-occupied territories was not defined, so Kyiv would probably lose them.

The UN Security Council permanent members – the United States, the UK, China, France and Russia – would be security guarantors. Kyiv wanted to add Turkey, while Moscow insisted on involving Belarus.

The Istanbul Accords would have reversed Western influence in Ukraine. NATO membership would be ruled out, while EU membership, although not clearly prohibited, would be problematic.

Given the Russian leadership’s irredentism, the Kremlin’s ultimate goal was Kyiv’s capitulation. Moscow would not be satisfied with Ukraine following the example of Finland, which was neutral and generally loyal to the Soviet Union after World War II.

What would these agreements mean for Belarus?

Łukašenka hoped for Minsk-3

Łukašenka considers the 2015 Minsk agreements, known as Minsk-2, one of his greatest political achievements. In February 2015, he hosted talks between Kyiv and Moscow in the Normandy Four format.

Minsk-2 improved his international reputation and became the starting point for Minsk’s rapprochement with the European Union and the United States.

Since February 24, 2022, the former French and German leaders, Francois Hollande and Angela Merkel, reluctant to admit their political mistakes and take responsibility for Ukraine, have played down Minsk-2. But Łukašenka is still proud of it and takes any attacks on it seriously.

In February-March 2022, he was close to replicating his success of 2015. Belarus hosted the first rounds of talks between Ukraine and Russia, but Kyiv insisted on moving the negotiations to Turkey. Minsk’s mediation mission came to an end.

Russia’s plan to include Belarus as a guarantor of Ukraine’s security was not a big secret. Łukašenka and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov spoke about it in March 2022.

For Kyiv, that was unacceptable in principle because of the role Minsk played in the first months of the full-scale war, allowing Moscow to use Belarus as a staging ground for invasion.

The inclusion of Belarus as a guarantor would demonstrate Russia’s power and emphasize Kyiv’s weakness.

For Minsk, which is considered in the West as a puppet of Moscow and a promoter of the Kremlin’s interests, seating next to the UN Security Council members would be a major success.

In 2015, Putin forced the French and German leaders to take part in the talks hosted by Łukašenka, an international pariah at the time. In 2022, the same pariah, who had just brutally suppressed protests, crushed civil society, committed an act of air piracy and engineered a migration crisis at the EU’s border, might have been admitted to high political society again.

Failed legitimization

The implementation of the Moscow’s plan crafted in the spirit of the “triune Russian nation,” with Belarus and Russia as security guarantors for Ukraine, would force the West to recognize Łukashenka as the legitimate governor of Belarus.

If the Russian plan was to succeed, it would have been a kind of payment for Minsk’s services to Moscow at the initial stage of the large-scale war.

But it failed. The Belarusian ruler reproached Kyiv for its recalcitrance and, on his own or Moscow’s orders, threatened it with tragic consequences if it continued to resist Russian aggression.

Łukašenka has been talking about a peace deal for two years now, but his statements ring hollow. The war in Ukraine has tied Belarus even more closely to Russia.

American, British and European sanctions have done some damage to the Belarusian economy. However, their impact should not be exaggerated, and Moscow’s assistance has helped Minsk to mitigate consequences.

The International Criminal Court has not yet issued an arrest warrant for Łukašenka.

His accusations that the collective West seeks to overthrow him are just conspiracy theories of the old dictator and his secret services. The door to the West is closed, but not yet locked.

The war in Ukraine has not spilled over into Belarus, allowing Łukašenka to bill himself as a “guarantor of peace and stability” in the country.

Tension between Russia and the West has only increased the importance of Belarus as the Kremlin’s only full-fledged ally in the post-Soviet space. In return, Belarus receives economic, military and strategic benefits, including arms and Russian tactical nuclear weapons.

Moscow makes no secret of its desire to establish full control over “brotherly Belarus,” and the chances of democratization in the country seem slim.

Although Łukašenka’s regime is only a Russian policy tool, the ruler has no reason to worry yet because Russia needs him and is satisfied with him, and Belarus is not the top priority for Moscow right now.

* * *

Two years after the large-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, Łukašenka has no reason to regret about the failure of the Istanbul Accords.

On the contrary, if the war ends on the Kremlin’s terms, it would only give a boost to Moscow’s drive to “gather Russian lands,” which would be a potentially tough challenge for the Belarusian ruler.