Three years after Belarus’ most turbulent presidential election, the country’s pro-democracy movement is still alive despite the suppression of mass protests. Everyday communication among activists and small initiatives can make a big difference in the future.

Three days of terror and five months of protests

Belarusians will associate August with mass protests for decades and will long remember the three days of shocking terror.

From August 9 to 11, security forces defied laws to use excessive brutal force against peaceful protesters. The government shut down civilian access to the Internet across the country, while security forces used tear gas, flash-bang grenades and fire arms to disperse crowds. Thousands were arrested, beaten and tortured.

The shocking violence sparked massive demonstrations. Between 300,000 and 500,000 people took to the street in Minsk on August 16 and August 23. Mass protests continued until December.

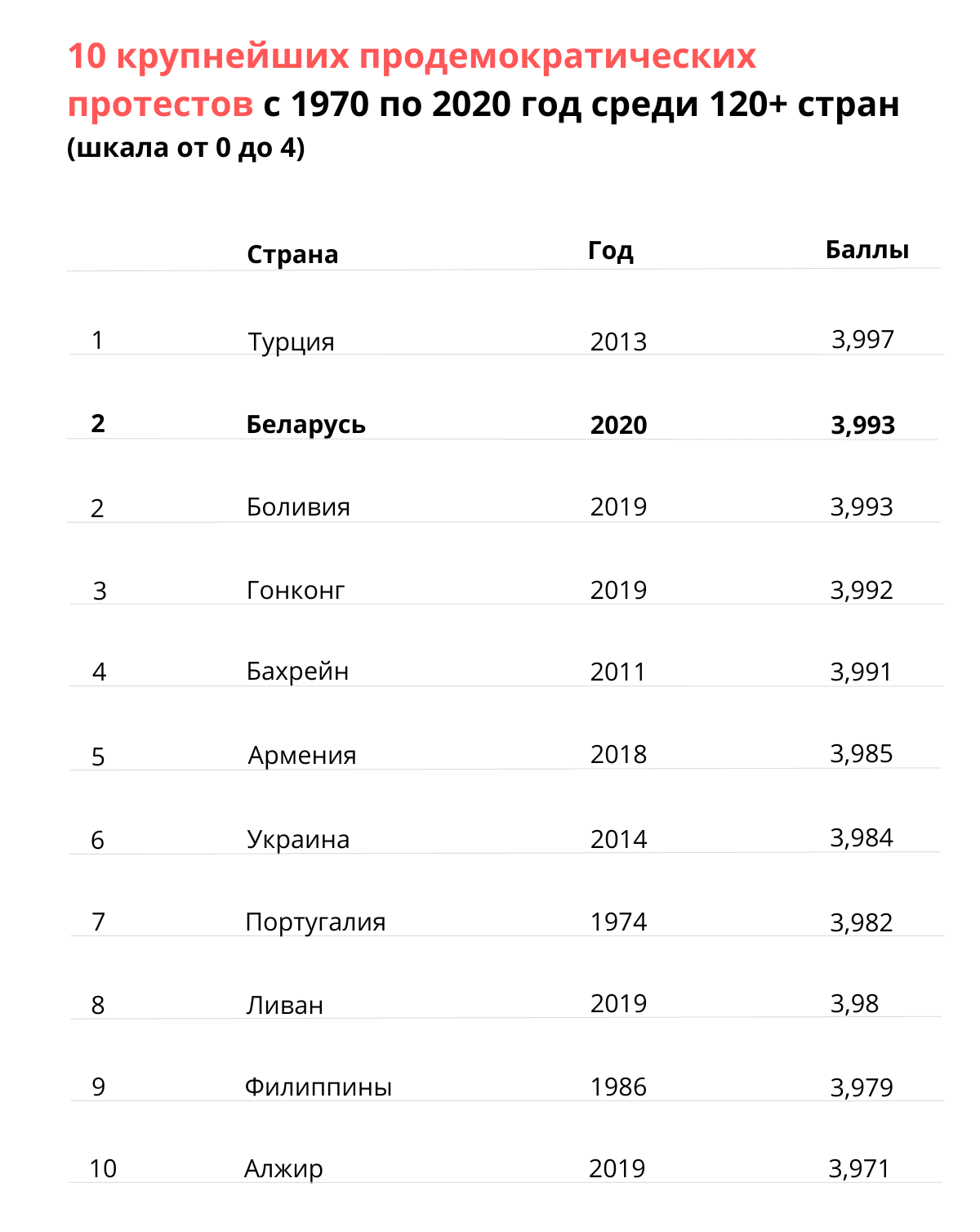

The V-Dem think tank estimated Belarusians’ mobilization for democracy at 3,993 points out of possible four in 2020. That is the world’s second highest mass mobilization score in the last 50 years (see the table).

Poland and South Korea: initial defeats

Why protesters failed to unseat Belarus’ authoritarian leader is still a subject of debate.

It may useful to see what happened in other countries after big failures. Let us go back to 1983 to examine the failed attempts to change the regimes in Poland and South Korea. Poland is geographically and culturally close to Belarus, while South Korea exists in a very different cultural and geographical context. This will help us analyze events from different angles.

In August 1983, Poland marked the third anniversary of the Solidarity movement. About 750,000 workers took part in the national strike in August 1980. Roughly the same number of sympathizers from various groups (intellectuals, the Catholic Church and students) actively supported the strikers.

South Korea in May 1983 marked the third anniversary of mass demonstrations for democracy and civil rights that had been brutally suppressed in Gwangju in May 1980.

It was hard to assess the impact of the Polish and South Korean protests in 1983, because the movements were crushed, while the authoritarian regimes survived and became more aggressive.

The questions, “Why the Gwangju uprising failed?” and “Why the Polish Solidarity strikes failed?” were as relevant in 1983 as the question, “Why Belarusian protests failed?” in 2023.

Democratic aspirations

Poland and South Korea have been sustainable democracies since the early 1990s. Now every story contends that the Solidarity strike or the Gwangju uprising was crucial for success.

Assessments based on the immediate collapse of regimes are not exactly accurate because success substantially depends on people’s aspirations and resilience.

The protest movements of both Poland and South Korea continued to make an impact. They rewrote their scripts deemphasizing public rallies for smaller events, informal communication and small initiatives to assist each other and pay tribute to victims of persecution.

When circumstances became more favorable, activists just stepped out of their kitchens to keep up pressure on the ruling elites. The end of the Cold War was the game changer for both countries.

Washington was able to pay more attention to human rights in South Korea, while the Soviet Union, preoccupied with the perestroika, paid less attention to support for the ruling regimes in allied countries.

In 1987, the South Korean regime made considerable concessions to the opposition, eventually resigning itself to democratization. A similar process occurred in Poland in 1989. It took seven years from the Gwangju uprising in South Korea and as many as nine years from the Solidarity strike in Poland to turn the tide.

Obviously, it is impossible to predict developments in Belarus based on Poland and South Korea. Still, the following conclusions can be made:

- Mass rallies, especially lasting and diverse ones, leave their imprint on the public mentality, and most importantly, on the mentality of the elite. Reprisals deepen the imprint, making protest narratives more dramatic and heroic.

- Heroism and martyrdom are inherent in some people, not in society or any considerable part of it. A decline in civil and political activism in response to severe reprisals is a natural psychological and moral reaction. It was observed in Poland during martial law and in South Korea in the first few years after the uprising.

- Reprisals cost a lot and complicate the regime’s internal and external legitimization, straining its relations with other countries. Repressive policies affect the economy and cause divisions in the elite. Sooner or later, the regime will have to review its methods to control society and reduce the level of intimidation. The cases of Poland and South Korea prove that society springs back to life during a thaw, motivated by earlier mobilization experience and the desire to complete the failed mission. Under favorable conditions, new mobilization for democracy has a greater chance of success.